Goya and The Disasters of War

We own one small etching by Francisco Goya, part of his famous series The Disasters of War. It has recently gone on display in the museum.

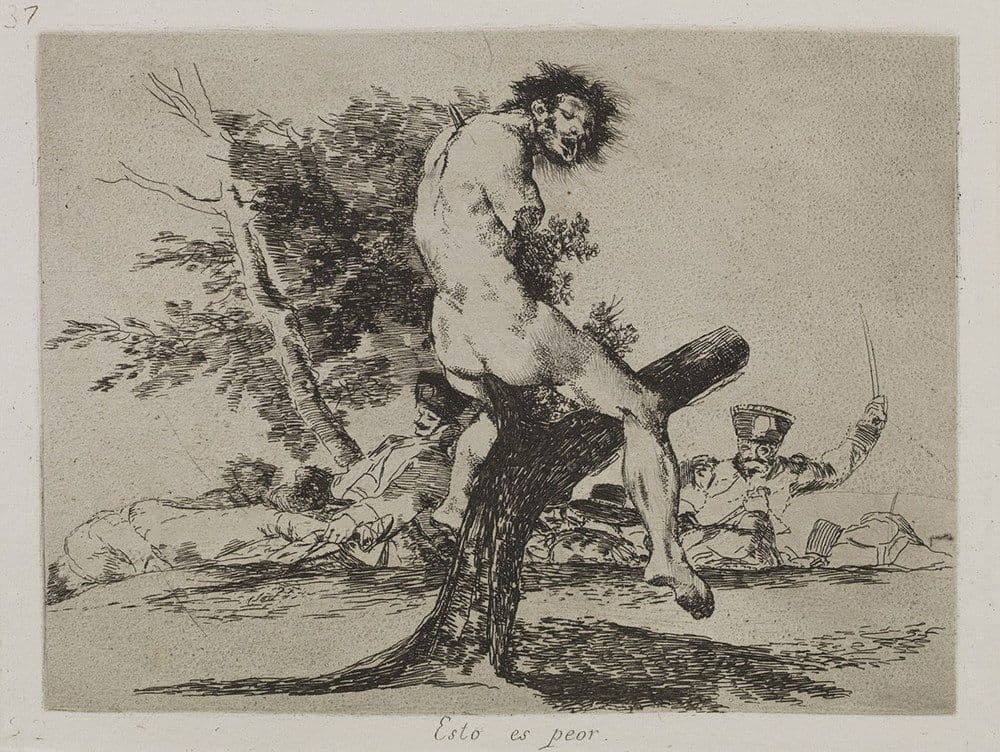

Esto es peor (This is worse);

plate 37 from the series known as Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War)

Made 1810-20; first published in 1863

Francisco Jose de Goya

My colleague Jane Clark writes in her ‘art wank’ text that Goya is referencing not just the Napoleonic invasion and occupation of Spain, but violent conflict in general. In our plate, she writes, ‘the mutilated body of a Spanish fighter is impaled like ghastly fruit in a tree’. The nude figure

derives directly from the antique: the Hellenistic marble Belvedere Torso sculpture which Goya had sketched during a visit to Rome years before. Where 18th-century cognoscenti saw ruined antiquities as evidence of a noble Classical past, Goya saw ruin as ruin and human nature as unchanging. There is no glory here. War, he suggests, is as timeless and innate a human trait as art.

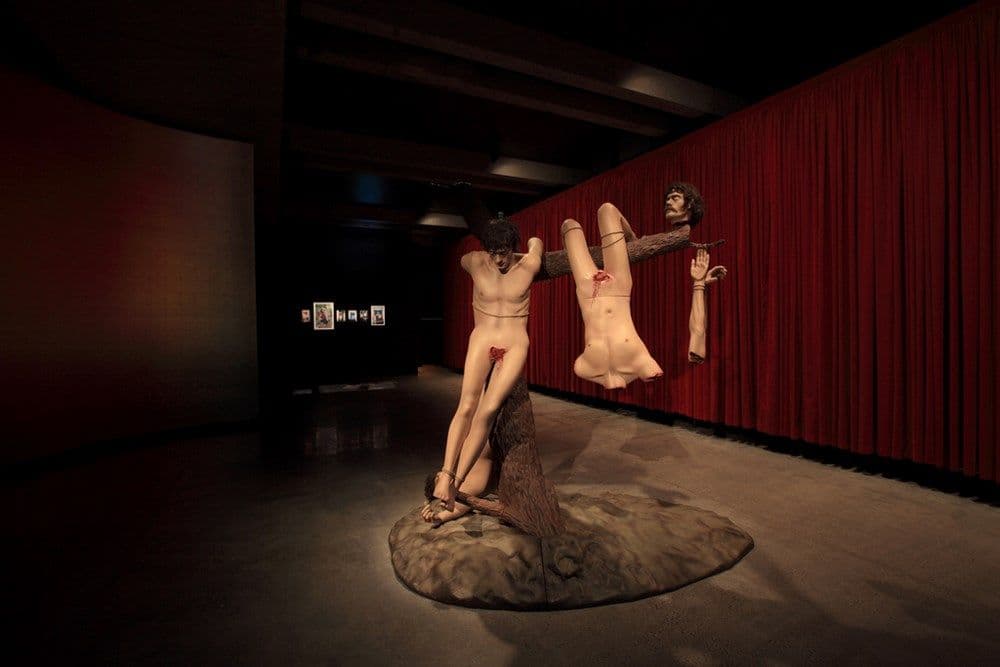

I know about Goya mostly via a pair of young-ish British artists called Jake and Dinos Chapman, whose sculpture, Great Deeds Against the Dead (1994), we recently sold. The Chapman brothers obsessively revisit Goya in their work; ‘like a dog’, as they put it, ‘returns to its vomit’.

© Great Deeds Against the Dead, 1994, Jake Chapman & Dinos Chapman

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

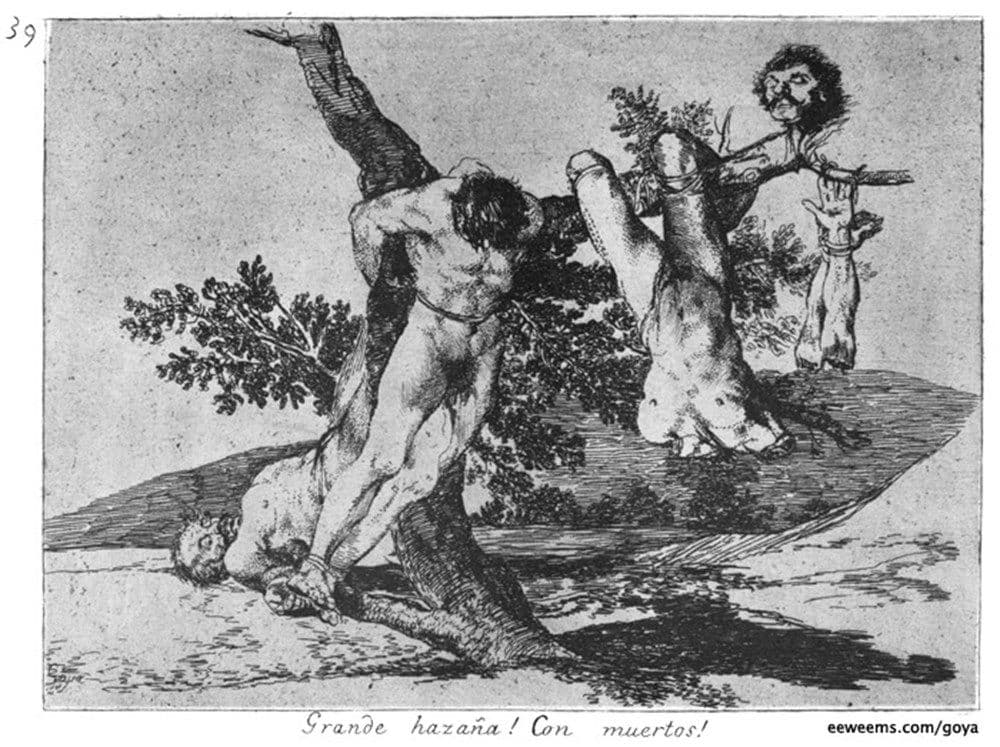

Grande hazaña! Con muertos! (An heroic feat! With dead men!);

plate 39 from the series known as Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War)

Made 1810-20; first published in 1863

Francisco Jose de Goya

Evidently, Goya is the kind of artist that makes a permanent mark on the mindscape of his descendants. What kind of mark? That’s impossible to say, because acts of creativity multiply upon inception, mingle and spawn, in ways that are not easy to discern.

I’ve recently been reading a great book (meaning one of universal significance) called The Ascent of Man by Jacob Bronowski, an account of the way man’s pleasure in his own skill and knowledge has drawn him ever upwards toward the heights of empathy and liberty of which he is capable. (We can talk another time about where all the women were during this ascent; I think watching Dr Phil). Bronowski’s is a nourishing, optimistic view of our kind, but he is at pains to point out that human cultural evolution is not a series of finished, polished cultural artefacts – the arch, the plough, the Theory of Relativity – but a ceaseless unfolding, a repetition and multiplication of ideas that infect the minds and behaviour of the human species as a whole.

Goya’s idea, here, is especially infectious. And that idea, as I see it, is not simply that ‘war is bad’, nor even that humans are capable of terrible acts of violence towards each other, although I agree that this is an important part of what he has to say. For me, Goya is telling us something astonishingly modern about ourselves, something he had no right to see so clearly at the turn of the nineteenth century, and something that is capable of fundamentally (gradually) changing who we are: violence is a kind of de-humanisation. I mean that in the general sense, in that to hurt someone is to deny their equal claim to life and liberty, their freedom from unreasonable pain. But I also mean that to be human is to be forever striving to balance what you want for yourself – the latent violence of your base desire – with what you want for the human race. It is in that way that being human is itself a process; a quick, and not a static, state. At our best, the spatial metaphor for the human condition might be a ladder, an ascent; at our worst – as we see, here, through Goya’s eyes – it is a dreary circle, terror numbed by repetition. Consider the titles of the Disasters of War etchings, sampled at random from the eighty-two in total:

The way is hard!

And it can’t be helped.

They avail themselves.

They do not agree.

Bury them and keep quiet.

There is no more time.

Treat them, then on to other matters.

It will be the same.

All this and more.

The same thing elsewhere.

Goya began the series at the age of 62; it was only published in 1863, thirty-five years after his death. For him, the weight of human suffering was too great; his career in many ways marks his descent from firm faith in order and reason into chaos, fear and disillusionment. But in the process he shows us that which sits at the seat of the human ‘ascent’: self-knowledge.