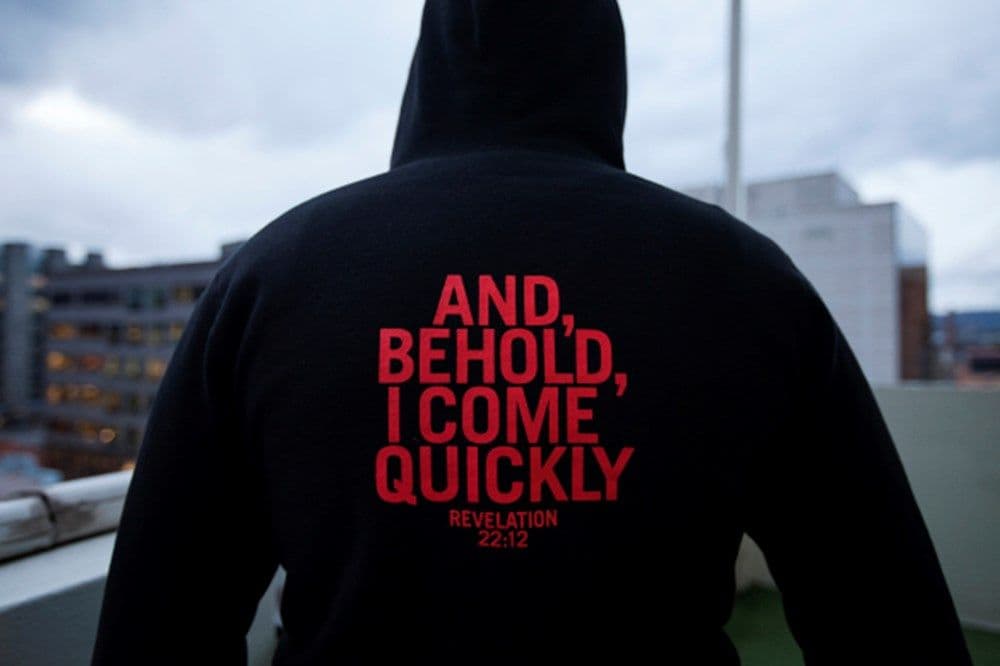

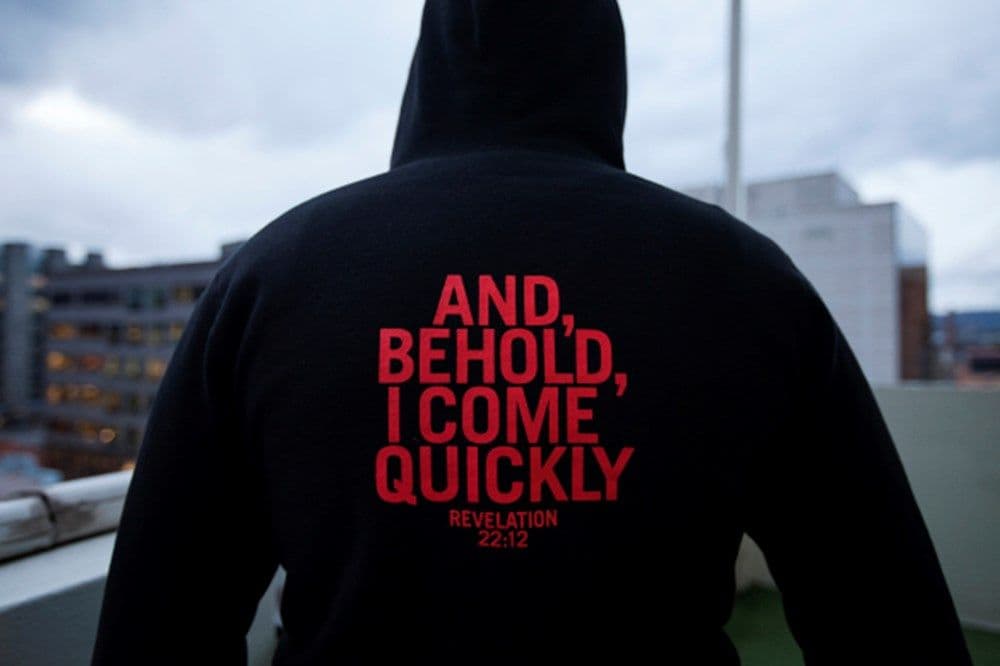

Going out with a bang

And, behold, I come quickly.

—Revelation, 22:12

So reads the back of this year’s Dark Mofo staff hoody. It’s from Revelation, the last book in the New Testament, which speaks, among other things, of the imminent apocalypse (literal or metaphorical—the jury’s still out) that will be unleashed with the Second Coming (Jesus: SURPRISE! Me again!). Revelation continues: ‘I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, the first and the last. Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates into the city.’ The grandeur of such proclamations has always stunned me; it’s like something out of a Michael Bay film. But we’re accustomed to this kind of thing, wallow as we do in pop culture’s hot mess of apocalyptic imaginings. No one’s exempt; the metaphors will always out, despite the pretensions of high culture and militant snobbery.

This revelatory snippet on the staff hoody—it has me thinking. It heralds the end of the world, instantly recognisable as a story of persistent human curiosity, but one that is endlessly open to interpretation. It proclaims the apocalypse, yes, but also confesses a propensity for premature ejaculation—a perhaps ‘world-ending’ event for some people and of a different variety. In perhaps not an entirely unpredictable manner, our interpretations of death—both big and little, planetary and personal—echo and warp as we mobilise them. Our photographer suggested the phrase for the hoody design, having seen the slogan adorning a painting of a lion and a lamb at the Odeon Theatre, before Dark Mofo took up residence there, when the theatre was home to a born-again Christian church. (Food for thought, perhaps, when you’re mid-debauchery at the Odeon for Dark Faux Mo. Remember, God’s always watching #catholicguilt.) The slogan has an irony in this churchy context, but I’m not going there. Self-deprecation is the order of the day, and it’s certainly not the first time MONA has co-opted a belief system for its own purposes (and I doubt it’ll be the last). In the painting, the mature-looking lion gazes fondly at the fluffy young lamb (would it be wrong to describe the lamb as nubile?), as ‘Behold, I come quickly’ intimates his intent (apocalyptic, carnal or otherwise). Poor little beast. Coincidentally, a Dark Mofo sign at the waterfront flashed, ‘WATCH FOR PEDS’, for the duration of the festival. Bright lights, creep city.

Painting previously at the Odeon

But recently the apocalypse, and its related scenario of a threatened and vulnerable world, has taken on a different texture. Politically, environmentally and geologically, the planet is being reframed, as humans rethink how they read the globe’s skin and viscera. ‘Welcome to the Anthropocene,’ proclaims The Economist, reporting on the early twenty-first century uptake of the term originally suggested by atmospheric scientists Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in the early 2000s. Basically (and I’m cheating—it’s not basic at all; it’s vast and complicated), the Anthropocene describes how Earth has entered a new geological epoch. Following on from the Holocene, the Anthropocene recognises the human species as an influential force of nature. Imagine a future where humans are extinct, goes the anecdote frequently used to describe the Anthropocene; if there was a geologist present in such a future, they would be able to trace the lasting human impact on the planet. Our marks, as they are, are here to stay. How do you like that for your vanity?

This is not to suggest that the Anthropocene explicitly envisages apocalypse (although, it is interesting to consider how that anecdotal extinction might eventuate). Rather, it frames a whole swag of political agendas1 and cultural fantasies2. But why imagine the end of the world as we know it? As a species, maybe we’re just plain freaking morbid, intent on sharing the love with an hysterical death drive. Freud might agree, which is alarming in itself.

The pay off, surely, is some sort of projected collective solace. Getting in early, before one hell of a punch line. On the opening night of Dark Mofo Films, I went to see David Michôd’s post-apocalyptic road movie, The Rover. Guy Pearce, with that hypnotic gravelly voice of his, posed a question to Anthony Hayes’ character:

Feeling the air when you wake up in the morning, when your feet touch the floor, or before that, when you’re lying there, thinking about your feet hitting the floor—the feeling you have. What does that feel like for you?

Maybe it was just Guy’s voice. Or maybe—forgive me—it tapped into something incisively and embarrassingly human. The desire to apprehend, and be apprehended by, another person. To escape your personal neuroticism and self-obsession, to imagine (if only for a moment) what it is like to be alive as somebody else and in their particular version of a material human body. It’s darker than empathy, somehow. And far more interesting.

Deep. Apologies. Is there anything more awkward than the expression of sincere sentiment?

I’m in the museum and I’m standing in front of Patrick Hall’s artwork, When My Heart Stops Beating, and it seems appropriate3. It’s my favourite work in David’s collection. Visitors to the museum have gotten engaged in front of this artwork, which I cannot for the life of me comprehend—do they see a hopeful sense of romance here?—because When My Heart Stops Beating seems to be more interested in the past than in an anticipated future. For me, it’s irreconcilably creepy and sad, and touching in a darkly bittersweet way. But it’s more than any ambivalent mess of feelings I might experience in front of these gleaming cabinets. It’s about what is no longer around and coming to terms with that; it's an attempt, if you will, to rectify such a predicament. Absent speakers intone their disconcerting chorus of ‘I love you’, just as absent writers reveal their intimate stories on the cabinet drawers (drawers that open like those of a morgue). The sense of loneliness is shocking, and it really hits me given the sheer constructed-ness of the artwork itself—those intricately built drawers and the façade of the cabinet fixed upon the wall. I’m embarrassed, now, to admit it’s my favourite. I sound like a total emo.

When My Heart Stops Beating, 2008 to 2010, Patrick Hall

Photo credit: MONA/ Rémi Chauvin

It’s like bearing witness to something, absent now whether through death, apocalypse or otherwise. I indulge myself even further, and imagine I’m that future hypothetical geologist, witnessing the earthly marks of the Anthropocene with its indelible remainders of previous lives. Marking time is a peculiar thing, whether romantic and sexual, or geological and planetary. A flippant, throwaway remark comes to mind, and it’s not so flippant anymore; it’s a genuine question, posed to the possibilities of a quickly coming future: ‘Who gives a fuck?

1 Here’s lookin’ at you, Tony.

2 For example: cli-fi, or climate fiction, is an actual thing. What an unfortunate abbreviation.

3 The other week, I went to MONA’s new community centre, and saw that When My Heart Stops Beating is no longer on display. Go home, Southdale, you’re drunk and you’ve ruined my blog.