Journey

It was my second time in Los Angeles. The first was after a flight failure and an accidental sojourn in Fiji, and before my first trip to Vegas. Vegas stripped me of my self-esteem and the little money I could muster, but the UNLV library gave me the ammunition I needed to attack horse racing. That first time I didn’t see much of Los Angeles, but the dingy little downtown shithole I stayed in, and the dingy big shithole that downtown was, bled out the entrails of my faith in the U.S. as the centre of the world. I had to avoid stepping in shit on the sidewalk (not the footpath). Human shit. In 1983.

So, my second time. Now I had some money, and I had Max, who believed in me. We stayed at a fancy hotel in Belair, ripped around in an open top car, bar-crawled on Sunset Strip, and shopped on Rodeo Drive. Los Angeles was still a shithole. In 1992.

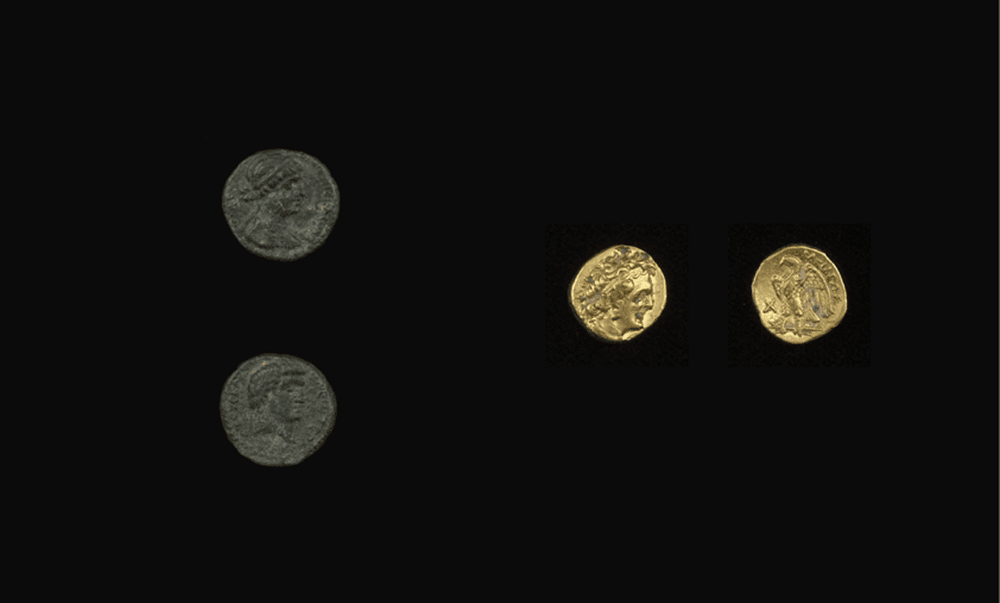

I went to Rodeo Drive to buy a metate, an ornate corn grinder from Costa Rica, and from before the time of Columbus. By 1992 I had some old stuff from Africa, but a documentary, Man on the Rim, had turned me on to the Americas. I went to buy stone, but I left with shiny metal. I bought coins. Coins of Egypt, coins of Italy, coins of Afghanistan. Coins made by Greeks, who dominated the ancient Mediterranean. Twenty-five years later I sold those coins, and a few paintings, to finance the construction of a new building at my museum, Mona.

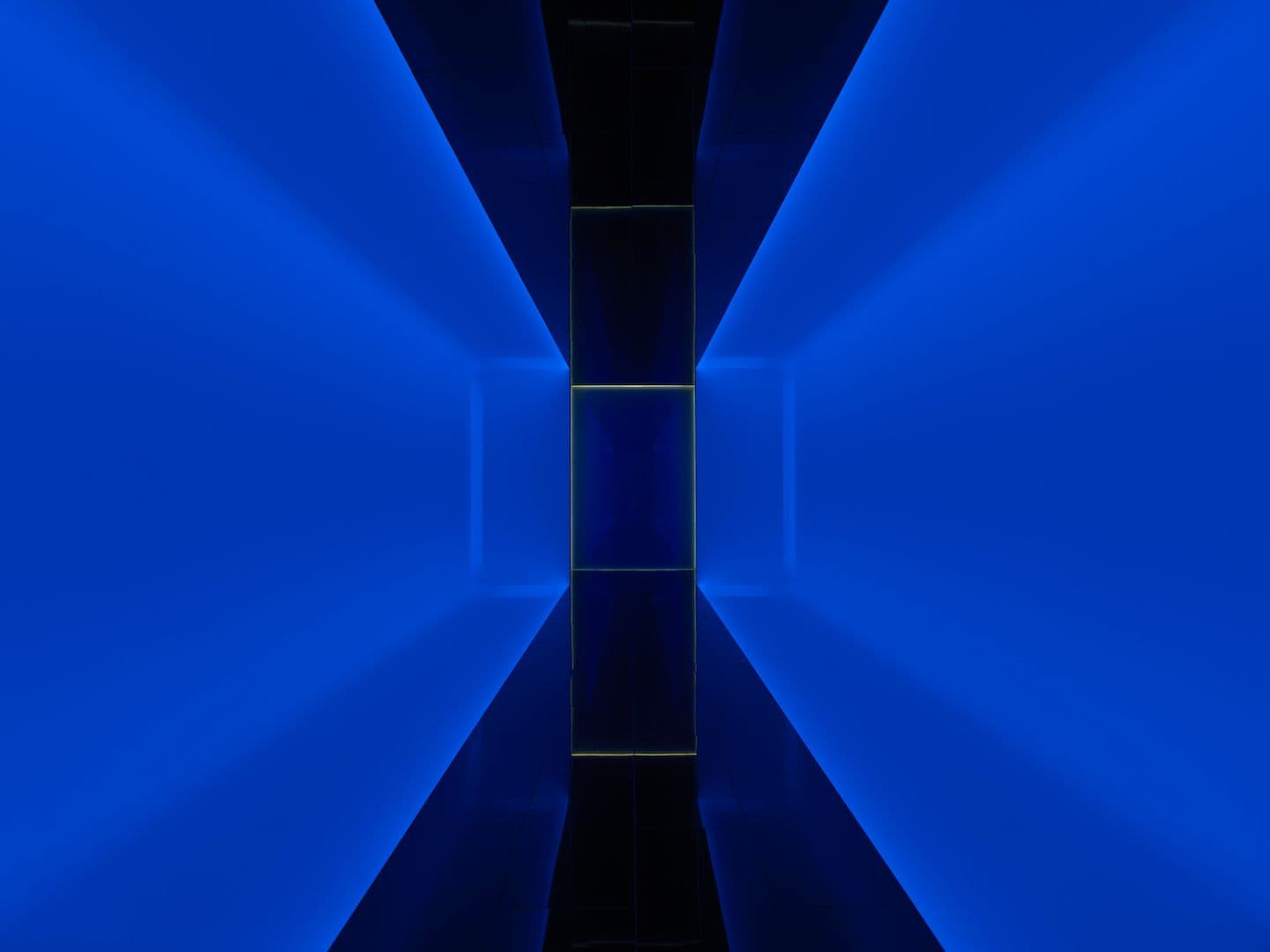

Pharos with Amarna, 2015, © James Turrell

I bought, and years later sold, coins of Ptolemy I Soter. Ptolemy was a general of Alexander the Great. After Alexander’s death he ruled Egypt as satrap and pharaoh. He also built the world’s first lighthouse, the Pharos of Alexandria, a Wonder of the World and a model for all lighthouses thereafter. Our new wing of Mona is a lighthouse too, but not one designed to warn ships of the risk of foundering on rocks. Our lighthouse is a testimonial to the power of light as art—not just as a medium for artworks, but as an object.

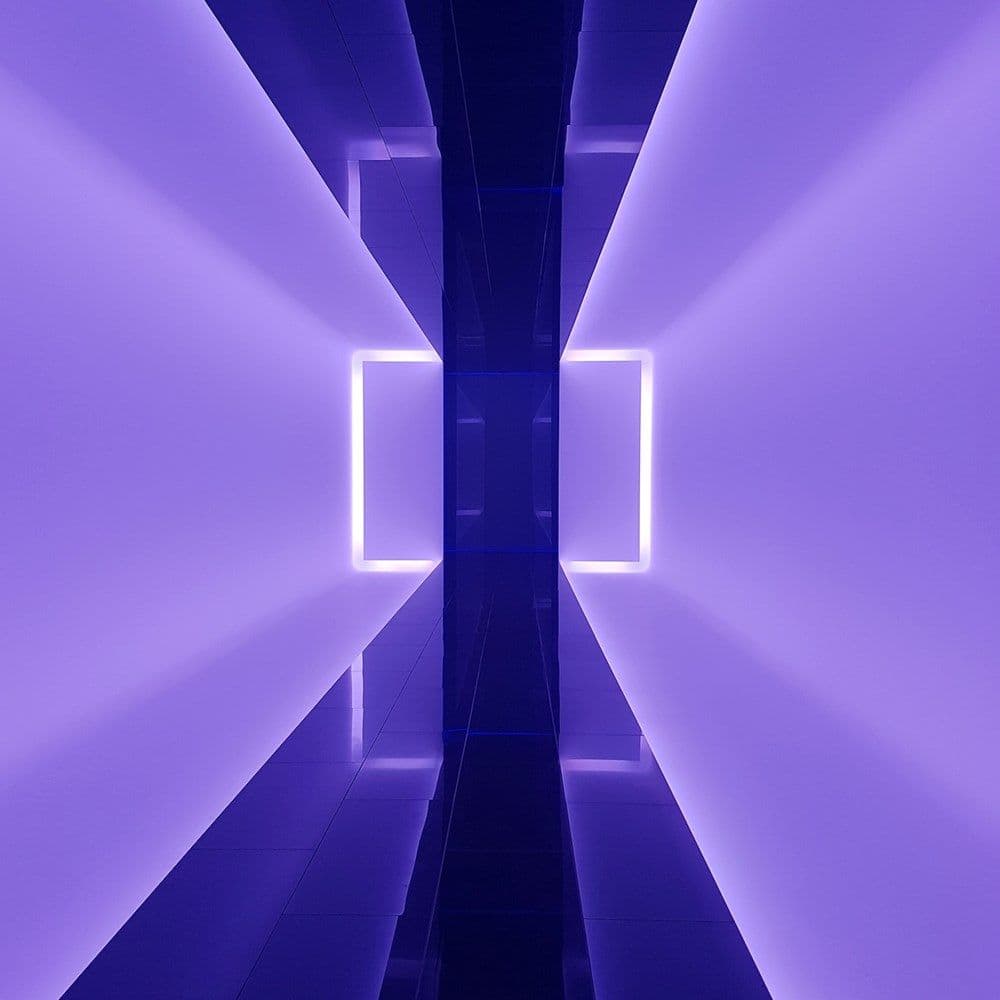

Event Horizon, 2017, © James Turrell

Event Horizon, 2017, © James Turrell

So after my second time in Los Angeles, I became a coin collector, and a fan of the sister-shagging, Greek-speaking Ptolemies. Because they wouldn’t speak Egyptian, the Rosetta Stone is in Greek as well as Egyptian, so some scholars can speak Egyptian now. And because they shagged their sisters and brothers, Cleopatra, Ptolemy Soter’s great-great-great-great granddaughter, became Pharaoh and the icon she is today.

It was my second time in New York City. My first had been after my first time in Los Angeles—whereas I found L.A. stultifying and forlorn, I found NYC exhilarating and uplifting. This second time I also found James Turrell, through the aegis of his Skyspace at PS1. I wanted a Skyspace as part of Mona, but James Turrell did not return my calls. In 1992.

Amarna, 2015, © James Turrell

Photo: Mona/Rémi Chauvin

A few years later James did return my call, and we got a Skyspace. He returned my call because he discovered I was in Hobart. Most Americans know nothing of Hobart but James knew one important thing. He knew that Friends, the world’s largest Quaker school, was here. James is a Quaker. Quakers believe in the power of light, and they believe in the power of education. So James came to Hobart, and while we built the Skyspace we schemed about six other works. Four of them are in Pharos. Two aren’t, as yet, anywhere.

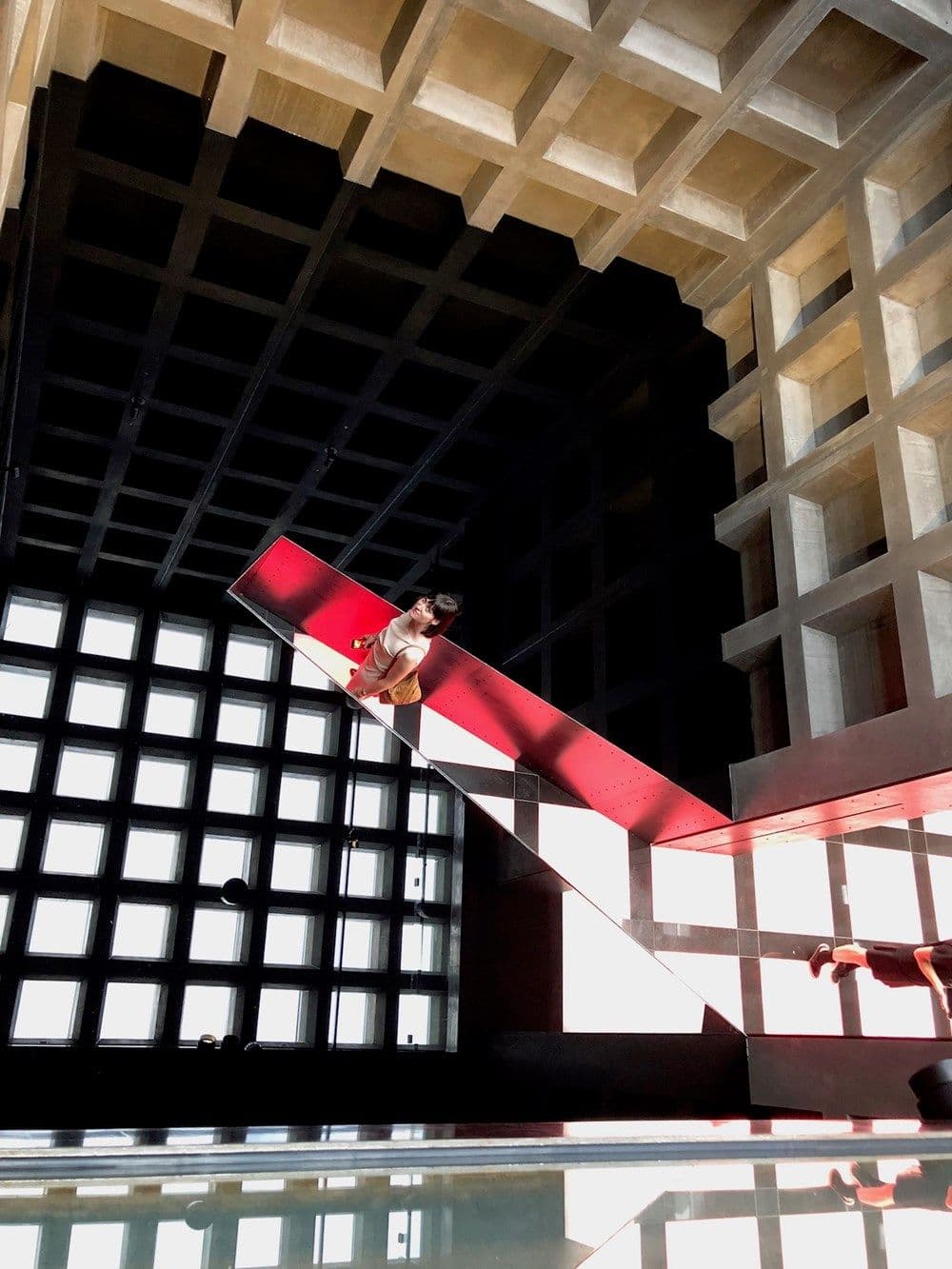

Beside Myself, 2017, © James Turrell

Photo: Rebecca Fitzgibbon

I am far from the first person to see the power of light, and to recognise the worth of Turrell’s work. Forty years ago the Dia Art Foundation contributed to a number of artists who were seeking to break the shackles of the gallery—they went West and sculpted the earth. James Turrell has been remodelling Roden Crater, a dormant volcano in Arizona, for over thirty years. Charles Ross has been working on Star Axis for even longer. Both are nearing completion, but even unfinished, both are comprehensively marvellous, and both touch the core of the human experience. For Pharos, Charles Ross is building us a room full of rainbows (unlike the rest of Pharos, it’s not quite finished—end of January is our target).

Spectrum Chamber (in progress), 2018, Charles Ross

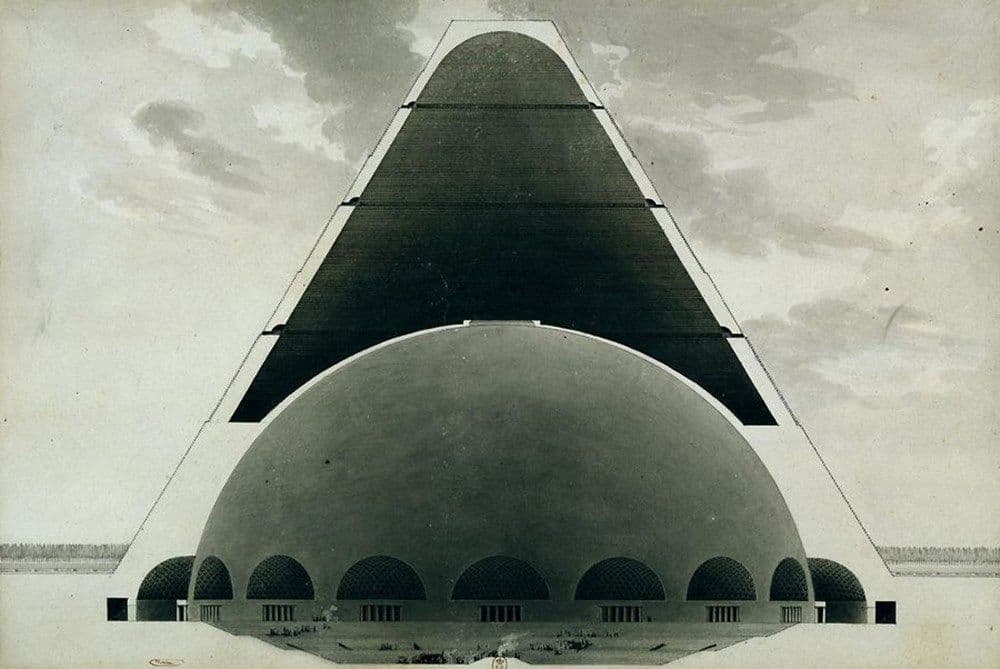

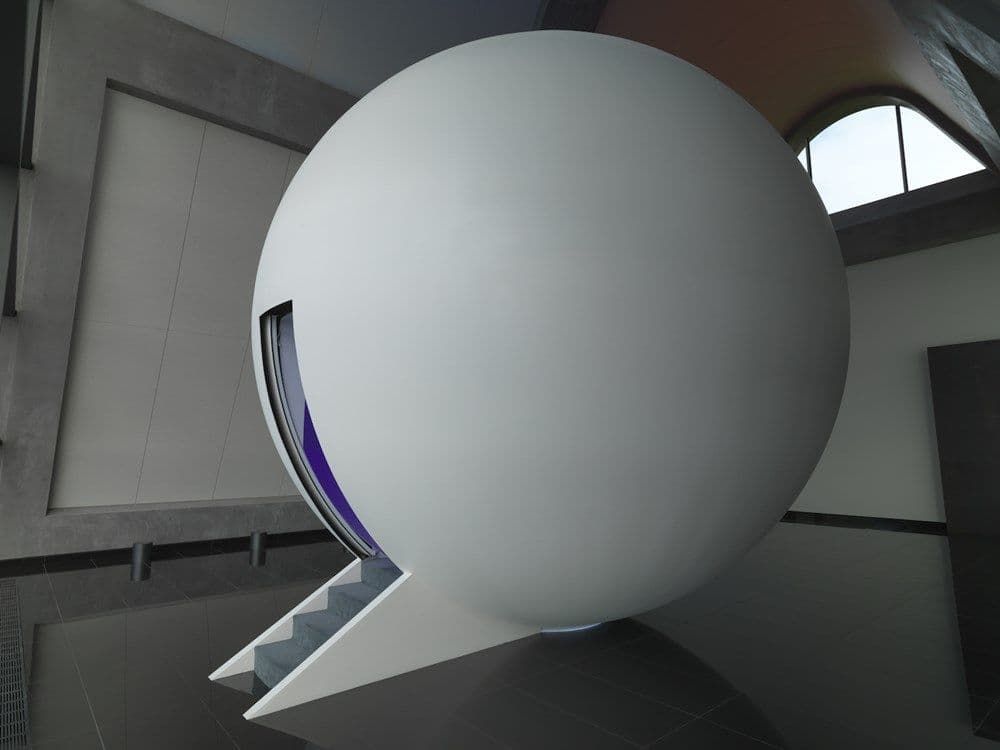

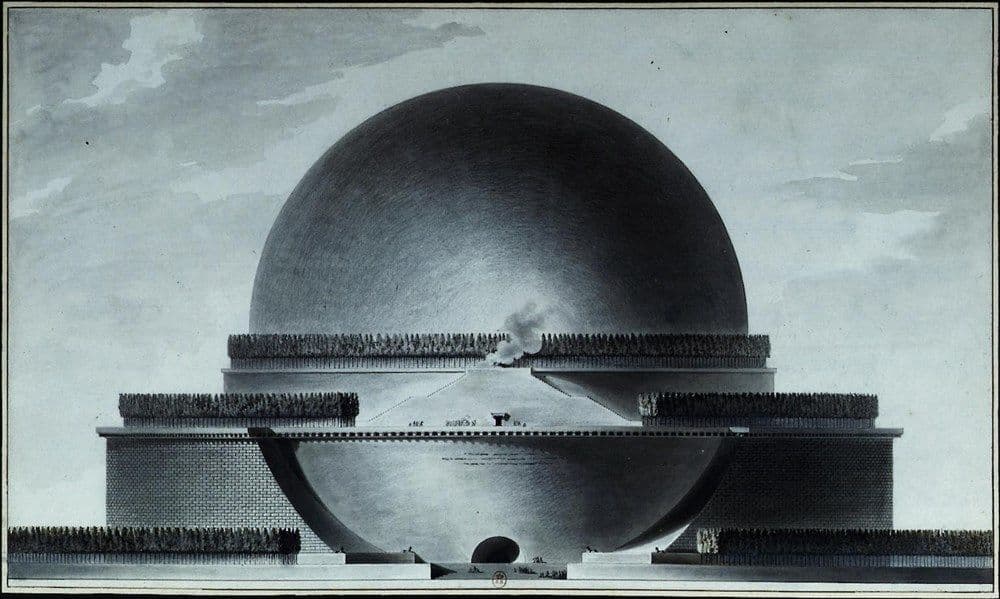

While planning and populating Pharos, I saw it as many, often contradictory, things. It is a counterpoint to Mona, a changeless thing, a legacy and a totem. It is a temple to light, to the history of ideas, a processional (think walking round the stations of the cross, or the Kaaba), and a journey through the birth canal. It is a paean to the theories of Huygens and Newton, and an architectural pastiche of the never-built memorial to Isaac Newton proposed by the phenomenal Étienne-Louis Boullée. Now, on the fifth morning of 2018, it is a congenial trap for the contemporary art sceptic, and a refresher course in being a child. Whereas Mona is intended to be an antidote to closed-mindedness, Pharos is open-heart surgery.

Unseen Seen, 2017, © James Turrell

Étienne-Louis Boullée, Cenotaph for Newton

Unseen Seen, 2017, © James Turrell

Étienne-Louis Boullée, Cenotaph for Newton

Unseen Seen, 2017, © James Turrell

Charles Saatchi isn’t very nice to his wives, but he has, inadvertently, been very nice to me. I bought some art from him—Jenny Saville, Chris Ofili, Damien Hirst—and I loved it, and I put it on the walls at Mona and others loved (and hated) it, and then I sold it for a lot more money than I paid for it. Saatchi, plus the coins, contributed a large part of the cost of Pharos. But Charles had another work I loved, Richard Wilson’s 20:50, a beautiful retelling of sump oil. I own it now, although Richard wishes I didn’t. And it’s here.

20:50, 1987, Richard Wilson

Photo: Scott Brewer

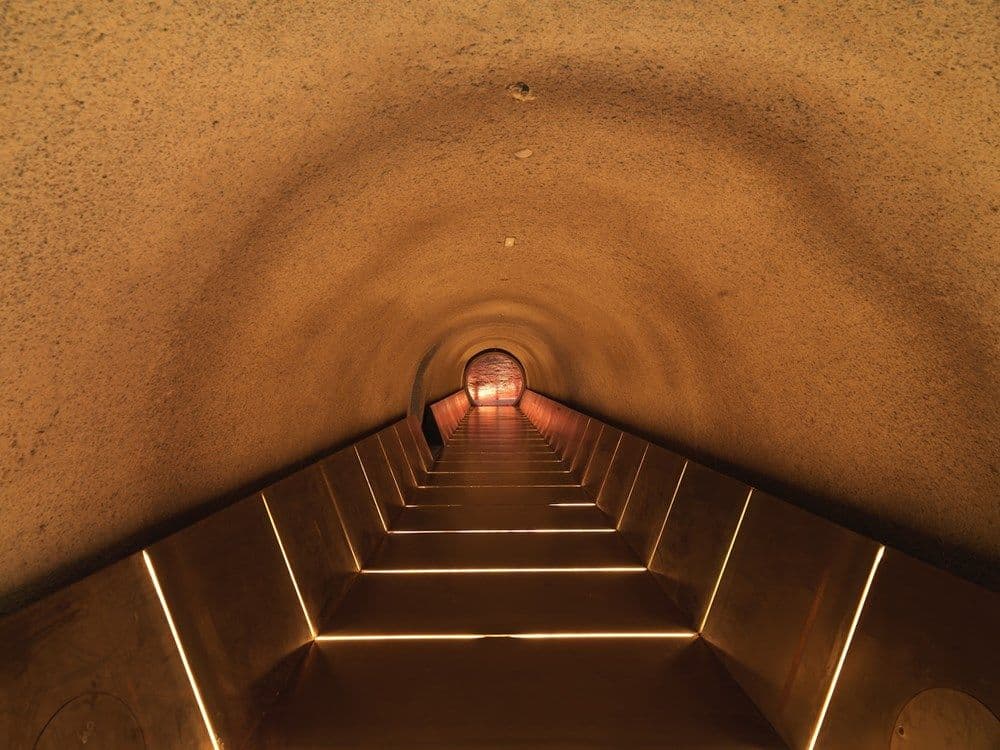

There is a spectacular Randy Polumbo chandelier, and I was going to hang it in the new tunnel of Pharos, but it would have hung too low, and the tunnel couldn’t be made any higher, because it has fire services above it. So Randy built us a grotto instead. It has become the selfie capital of Mona, so even those who don’t come to Mona will see it in their friends’ Instagram feeds.

Grotto, 2017, Randy Polumbo

Grotto, 2017, Randy Polumbo

There is other stuff in Pharos, a thrashing machine from Jean Tinguely, and a video portrait of Abraham Lincoln as an incapacitated robot. There’s Spanish food, and a frustratingly incomplete bar (the German company tasked with delivering the bar glass stopped answering the phone...). And there will be more stuff as we finish the tunnels this year. It’ll keep going while I keep going and the cash keeps flowing.

Memorial to the Sacred Wind or The Tomb of a Kamikaze, 1969, Jean Tinguely

Lincoln, 1990, Nam June Paik

Faro Tapas with Unseen Seen, 2017, © James Turrell

Faro Tapas

Faro Tapas

In the 1970s Ivan Illich, Catholic priest and provocateur, argued that technology came in two potent forms: the convivial and the manipulative. Manipulative technologies disrupt the ecosystem in which they are employed: cars, for example, require roads and refuelling. Convivial technologies, like phones, Illich argued, bend to the will, but are otherwise invisible (this was in the 70s, remember). He believed that technologies should be designed purposefully to be convivial. I designed Mona to be manipulative—I want it to thrust itself into a visitor’s worldview in the same way that God is at the centre of the experience of a medieval cathedral. Mona isn’t benign, it’s a leech, or a tumour. Pharos is a daydream, or a symphony. Pharos is a pleasant distraction while going for a walk. Pharos may be uplifting, but it won’t change any minds.

Unseen Seen, 2017, © James Turrell

Photo: Rebecca Fitzgibbon

Grotto, 2017, Randy Polumbo

It was my second-last time in Los Angeles. I was there with my not-quite wife, Kirsha, and L.A. is a city she loves. She spent her first few years there, and many years since. I tried, I really did. I went for long walks, and I went to museums, and even back downtown for the first time since my first visit. And it was better, much better, but it still wasn’t good. And then I went to a James Turrell exhibition at LACMA, and in Turrell’s perceptual cell the cacophony of bland was overwhelmed by the light in my mind. I could see the inside of my eyeball, but also the colour of my thoughts. And then the world again intruded—my phone rang. I ignored it, but it kept on ringing. That phone, not so convivial now, told me that back in Australia, a rock had fallen off a building, and struck my eight-year-old daughter on her head. I flew back to Australia, not knowing to what I was returning. And on that flight I could feel every moment, grasp every sensation. Now I know what I want Mona to be. I want it to be that flight, hard but human, desperate but lyrical. And I want Pharos to be the doctor, the one who greeted my frenzied entreaties with, ‘It’s rough, but everything will be okay.’

Tunnel to nowhere

Header image: Beside Myself, 2017, James Turrell

Photography: Mona/Jesse Hunniford