Five prejudiced affairs with Mona (or, Anica and Mona, sitting in a tree)

1. The art of knowing whether you are flirting

or

The art of consuming modern art

You never know what to expect, when you first walk in. Something, nothing. Something that turns out to be nothing? Nothing that becomes something? But that’s part of it, it’s part of what you crave. The not-knowing, the possibility, the risk, the anticipation.

Or, you walk into it, always, knowing that you want something. Anticipating. Breath-held wonder and the greed for Meaning. For something Beyond. For Something.

Forgetting that you always bring something, too. Into that space filled with sound and furious signifiers. A look, a wink, a glance, a colour, an ellipsis of thought...

And sometimes it feels like there is a lot of empty space here. Whatever that means. It doesn’t mean space with nothing in it. It just means space where what’s in it isn’t something you know how to find. But that’s part of it too. And if you don’t crave that, then there’s no room for you to become anything else.

Every visit, every interaction has a memory of the last, and the last-but-one, and the very first, and all those between. And not just your own, but everyone else’s too. Whether that makes you feel good or not. You can never be independent of it. You don’t even have to listen carefully to hear it. There’s nothing new here, and nothing old either – everything exactly as you see it as you come to it at this moment: the wink, the shadows, the abstract moment, the ambiguous words.

You ignore what doesn’t speak to you. Dismissive. (And yet you still think you’re better than the girl beside you who snaps a photo, winks a wink, pretends to see something, sees nothing.) You sidestep around the arti/fact for a moment, you make it what you want it to be, you read it, you act on it, you understand it, you live by it, you love by it, you are – for those moments and their repercussive pre-dawn awakenings – defined by it, and it by you.

And then you turn a page, a corner, a blind eye, and you discover a new star (or disavow an old one – all your past loves are eventually Plutos).

I stop near the end, as always, to check that my heart is beating. As always, it’s not. As always, I pretend I don’t care.

Pulse Room, 2006

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

Photo credit: MONA/Leigh Carmichael

2. Don’t touch

There’s water dripping through the walls here. I’ve never noticed before. I’ve read about it, in all those things that people write, but I’ve never seen it. That interests me. To know about a thing and to touch a thing are not the same at all. At all. Peter Carey, in the voice of Lucinda, once said as much. I bookmarked it – a real bookmark, subcutaneous in the skin of a book, not a click on a word that once meant something real. Before ‘bookmark’ was a verb in my vocabulary. When it was still a noun I could touch. I held that page, with my bookmark, and came back to it over and over. And over. I could still find the page, I think, just with the curve of spine from so many visits.

Lucinda’s knowledge was about sorrow – about suffering and conceiving of suffering. Mine is about something else. About seeing what you want instead of what’s there. At least I think it is.

(Well, wouldn’t you touch that wet wall?)

3. The idea of absence

This place is just filled with your voice – literally, literarily. It’s all you. I can’t imagine how it feels to experience this place without you. On my own, with anyone else.

I think I’ll visit here when you die, and I’ll forget what it means to die: it won’t make any sense because you will be here and everywhere and I won’t understand the idea of absence.

That’s assuming that you die first. And I don’t know why you would. Maybe I’ll die first. And if that’s what happens, then I’ll come here after I die. I’ll haunt your words and your presence here and then you won’t know what it’s like to be here without me.

4. The blind leading the blind (after Peter Buggenhout)

A great hulking thing hangs above me. I think maybe it’s art. Or maybe dread. Or maybe love. It is huge and blackish in the blackness, embarrassed by its own size. An apologetic, deformed monster trying desperately and writhingly to disappear backwards into cracks nonexistent: a mutant spider, an octopus, without the proper experience of its species, to disappear into cracks. For every limb it squeezes into one corner, two more vomit themselves out of another: messy, dripping, scrabbling for purchase on the surfaces, alive yet utterly inert. Grasping at the ceiling, ashamed of its own clumsy bulk, its corners are impotent and its curves broken. Its rusting creaking groaning strength is a kind of unkind joke against its ludicrous body. It is Kafka’s Gregor, horrified by its own existence. I am afraid to stand beneath it. It is some kind of nightmare – to itself?

And also I want nothing more than to be closer to it in the half-light, for it to somehow ingest me, excrete me, validate me.

5. Why shouldn’t we?

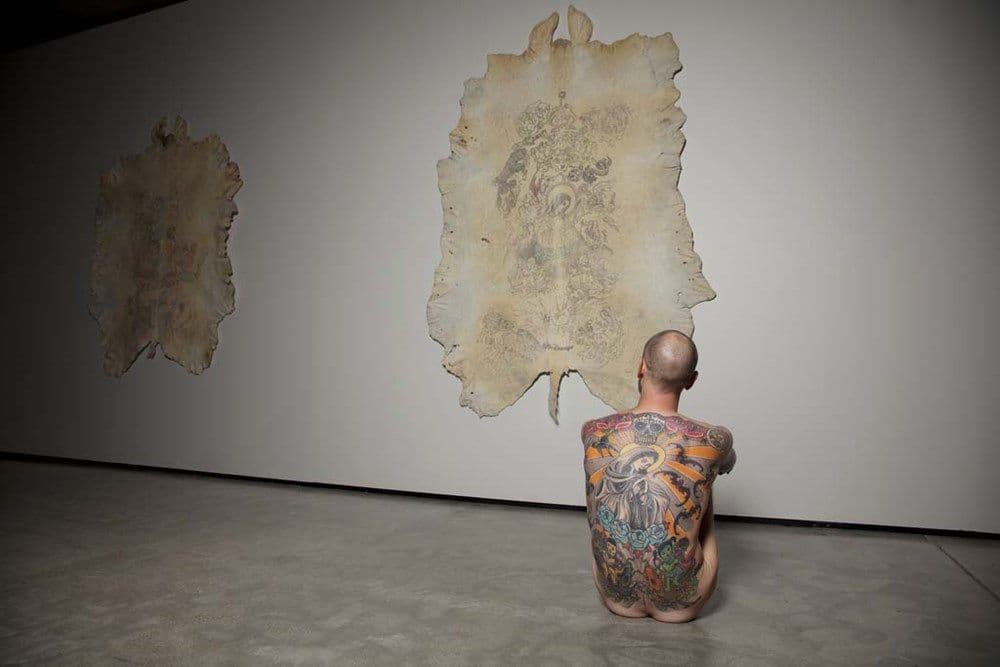

I finally manage to book in for one of Tattoo Tim’s tours of the Wim Delvoye exhibition – his third-last tour. He’s had a few days off, and he says he hasn’t been so nervous in a long time. He’s buzzing. He greets us all individually, welcomes us, tells us that he’s not here to explain the art, but just to tell us a story. His story is his way of giving us the gift of recognising what he calls the ‘beautiful absolute irrelevance of our existence’. And somehow I think I understand what he means

He talks to us for seventy minutes, in between the pigskins and the sharp points of the laser-cut steel. He is funny, self-deprecating, self-important, performative, honest, naive, cynical, charismatic, entrancing, exploding with energy. I suppose he has a lot of time to come up with clever things to say, sitting for five hours a day on his plinth with his tattooed spine towards his audience, his eyes on his one small white speck in the middle of the black window shade. During the tour, we never once see the tattoo. But we see the impact of it on his life, on his experience of being in the world. And it’s bizarre and mundane all at once.

Everything he says to us is engaging. But at the end, in the dark room standing against the projected reality of Delvoye’s Art Farm, where the tattooed pigs grunt and shove and scratch and sleep, he gets to the part that hits me most. He orates a kind of fanatical frisson of absolute adoration for Mona, and that’s part of his story now too. He tells us, from the outside, that ‘everything has changed here in the last 14 months’ – this city isn’t the same one it was before. I could not be more convinced by his arguments.

At the end of Tim’s tour, I’m shaking. He’s articulated a passion for this place that I’ve heard around me since the museum opened. I hear it everywhere – in the museum, away from the museum, on airplanes, interstate, in supermarkets, everywhere. It’s an uncontainable and weird sense of ownership, pride, excitement, gratitude, wonderment. I feel it too, and I resent it. I hate feeling so sentimental and I don’t want to be one of the anonymous masses who somehow feel that since it has entered our lives, we now have some righteous connection to this place. Last year I went for the first time to MoMA, the Guggenheim, the Neue Gallerie, The Dali – so many wonderful American museums, but all the time I was holding this secret smugness that I live in the place where there is Mona. I couldn’t wait to come back and visit. It feels unsophisticated to experience so much joy about a place, especially this place. I am embarrassed by my passion for this place. But why shouldn’t we feel in love – what’s so incredibly wrong with being joyful?

Mona has done something to me that nothing in my life has ever done before. It’s connected me to people I don’t know and don’t ever want to meet. It’s torn a gash in the emotional, creative, psychological space/time continuum – a great fissure that allows glimpses into everything we dream of, and forget to dream of, beyond the everyday. The things we search for in love, in religion, in our unknown selves. Meaning, connection, extraordinary grief and extraordinary radiance, and – more vitally – things wholly intangible, but so deep that they lift us away from everything else.

I thank Tim; he hugs me. I walk away fast, because I need to find a dark space to be alone and cry my guts out, because I can’t remember the last time anything made me feel so alive.

When I come back outside into the air, the steady rain takes me by surprise. But I don’t remember, anyway, what kind of day it was when I went inside. It was a million years ago. As always, when I leave here, I’m new. Better. Taller. Hungrier. More alive. More certain. More uncertain.

That’s all.

Anica is a writer, editor and critic. She has an ellipsis tattoo and if you notice it and identify it correctly, she might fall in love with you. We don't know how to pronounce her name.

Tim, 2006 – 2012 (ongoing), with various pigskins

Wim Delvoye

Photo Credit: MONA/Remi Chauvin