Gilbert & George: a critique

I’ve been trying to work out what I think about the art of Gilbert & George. There is much that should not be taken at face value of course, but the democratic element of the work – their desire to speak as clearly to taxi drivers and café owners as to snooty gallery-goers – is genuine, and it is successful. (You shouldn’t call it ‘work’ though, it’s too wanky; they insist on ‘pictures’.) You don’t need any special knowledge to look at the pictures, nor even to think very hard. Their desire to be anti-elitist is borne out in their art critic of choice: a guy called Michael Bracewell, who has been writing about their art for years, and whose essays – no less than eleven – can be found in the catalogue on sale in our bookshop (and here), along with an introduction by David Walsh and foreword by Olivier Varenne. Sometimes, so-called anti-elitist artists are pipped at the post when it comes to criticism of their work: they insist on art wank in their catalogues and so forth, because they think it legitimates them, or something. Bracewell eschews such wank for a warm (if sometimes repetitive) humanism. And – like the artists themselves with their suits and ties and their pleases and thank-yous – Bracewell’s texts can be misread as quaint; in fact, they are progressive for their refusal to bow to the taste and fashions of the moment.

This brings me to probably my favourite thing about the Gs. They turn the idea of ‘radical’ on its head. They say the reason they adopted their trademark ‘conservative’ look and professed their love of Maggie Thatcher was to beat their own path, away from their bohemian peers. I am similarly irked by the seemingly compulsory politics of the gallery-going demographic, parts of which confuse ‘radical’ with ‘left-wing’. Of course, often, the two overlap. But ‘radical’, to me, is not a fixed set of beliefs, but a willingness to think things through independently, and to entertain an idea on the basis of its merit and not its popularity. They are not really old-fashioned and quaint of course, nor are they true lovers of Thatcherite politics – beyond, perhaps, a belief in the creative capacity of the individual (this is purely my reading, they have said nothing to this effect that I am aware of). But it was important, back in the 1960s when they met, to mark themselves as outsiders – for two reasons. Firstly because it emphasised their desire to break out from the uniform modernity of their art-school generation: the muted tones, the circles and squares, the denial of emotion. It’s easy to lose sight – when you’re looking back along the arc of art history – of how brave it is to do something different. (The extent to which this ‘something different’ matters to them is borne out by a fifty-year commitment… More on that below.) And secondly, in adopting the suits and the faux-stuffy manner, they are making a simple but effective point about the way in- and out-group boundaries are policed in the art world. To belong to the cultural elite, you must meet certain criteria, such as progressive politics, bohemian manner, and love for difficult and densely theoretical art. (For a hilarious take on this, read Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word). This is set up in opposition, as Wolfe points out, to stuffy middle class values: pretty pictures, politeness, conservative politics. This desire for elite cultural status on behalf of the viewer, along with the artist’s desire to be more and more radical, creates a kind of feedback loop that has a real impact on the cultural evolution of art (and, as we will consider in an upcoming exhibition, can be traced to our biological evolution as well).

To stopper this feedback loop, and go against the grain, was truly radical of Gilbert & George. But that was in the 60s. What about now

Around the time of the exhibition opening a few people commented to me about how the Gs are such a perfect fit for Mona. I can see why they would say that – the subject matter, the bright colours, as well as the desire to ‘piss off academics’ as David would put it. But for much of this process, I have been preoccupied by the way they are different to us. And in thinking more about this, I have reached my conclusion about the art of Gilbert & George: I respect it, but ultimately, it’s not for me.

In my capacity as writer for the Mona marketing team, I was a little slow to work out that the Gs wanted, basically, to colonise us: to implant their entire worldview onto Mona as a passive platform, in everything from text on our website, the style of font we use, eccentric punctuation, etc. This is part of their long-standing way of working: they design, curate and execute the entirety of their exhibitions, on the stated basis that they, not curators and gallery directors, know what the public wants. I found this a little bothersome at first but then I got the hang of it. It was good for us, I think, to try this different way of working: quite often we ask artists to join a choir in a sense, to let us sublimate (respectfully) their intention to the overall ‘experience’ of the museum. It was an interesting experiment, and one that prompted us to think more clearly about our usual methods.

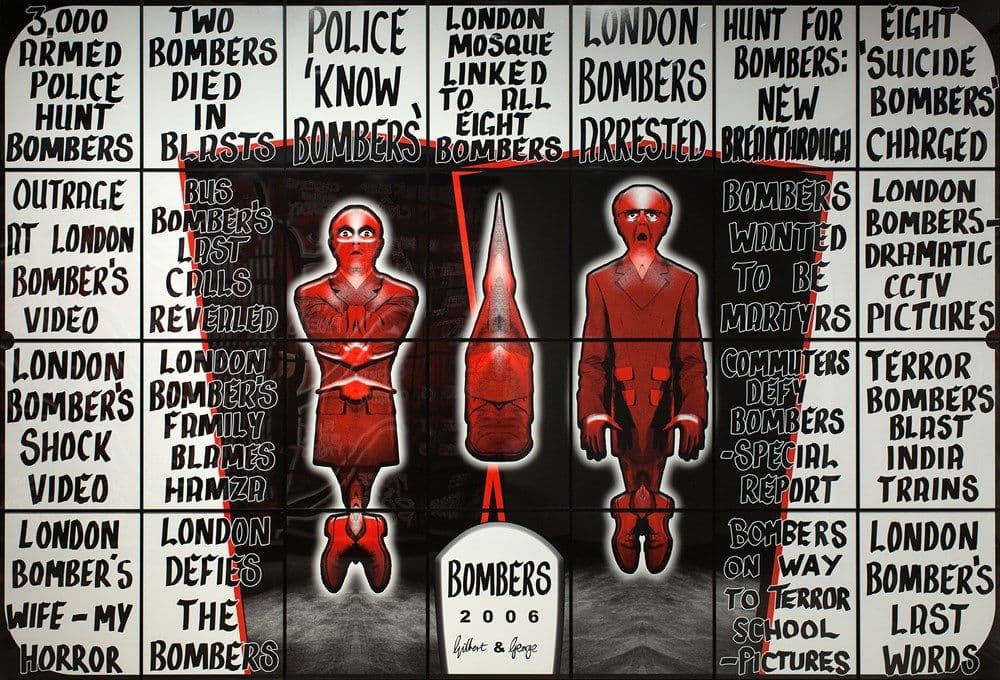

But as the process wore on, I began to wonder why it was so important to them to be so unbending. It fits within the ethos of their work, which makes stasis (somewhat factiously) a kind of ideology. They famously eat at the same Turkish restaurant every night, and avoid cultural input like theatre and films, in case it distracts them from their distinctive view. And do the pictures themselves reflect stasis? The subject matter has changed a little over time, as has their use of colour and composition; they switched seamlessly to digital photographic processes in the early 2000s. But the essential idea remains the same. They pride themselves on this: ‘The world has changed,’ they tell us, ‘but our pictures stay they same.’ And I know what they mean. Think of the SCAPEGOATING PICTURES (they like it written in capitals) that dominate the space as you first enter the exhibition at Mona. Women in burkhas – neighbours from their home in London’s East End – stare at us or thwart our gaze, alongside the artists themselves, who are variously menacing, and/or fragmented into little pieces, as though destroyed by the ‘bombs’ that dot the pictures. They are not really bombs of course, but nitrous oxide canisters (hippy gas) that are apparently strewn around the streets near their home. In the wake of the recent Paris attacks, these pictures are breathtaking. They capture, for me, a central ambivalence at the heart of our western stupefaction in the face of extremism: How can we begin to reconcile our love of diversity and tolerance of difference with our creeping awareness that dogmatic thinking – including that which motivates religions of all kinds – closes down the free play of the human imagination, giving rise to totalitarianism and terror? I don’t know the answer but I am pleased the Gs are worrying about it with me. And I respect them for not running away from it – literally, in their commitment to live among and depict their multicultural and multiracial neighbours, and to inhabit all the hypocrisy and contradiction to which this gives rise. I sense, here, the beginnings of that ‘moral dimension’ they claim for their art.

Gilbert & George

Born 1943 in San Martin de Tor, Italy and 1942 in Plymouth, England; live and work in London.

Gilbert & George: The Art Exhibition, on display at Mona until March 28, 2016.

Photo Credit: Mona/Rémi Chauvin

Image Courtesy Mona, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

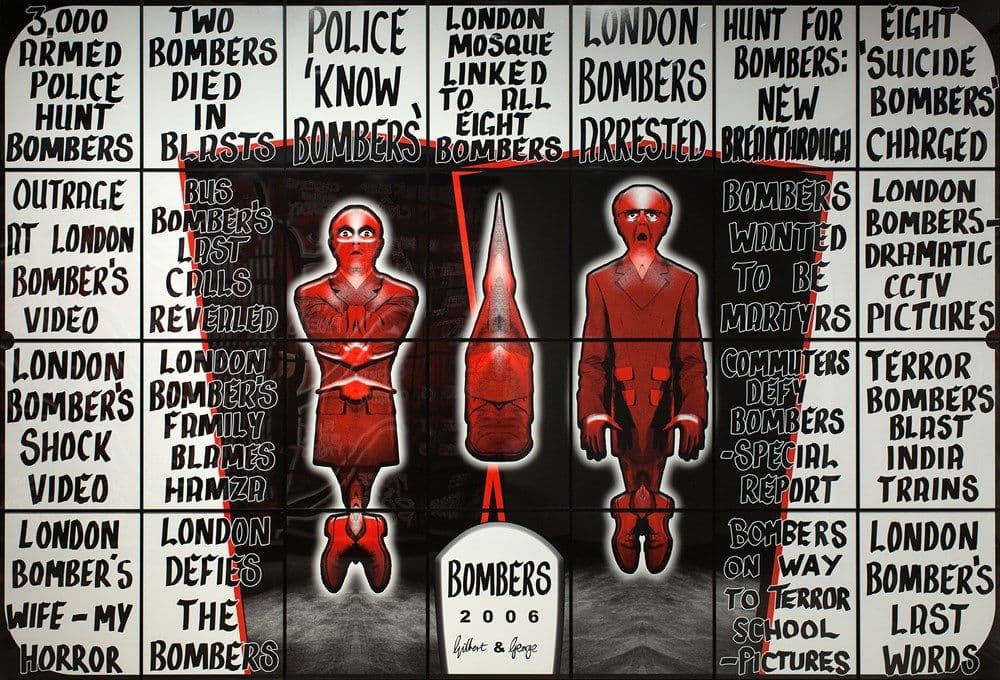

BOMBERS, 2006

Gilbert & George

(Born 1943 in San Martin de Tor, Italy and 1942 in Plymouth, England; live and work in London)

Mixed media

Courtesy of the artists and White Cube

Photo Credit: MONA/Rémi Chauvin

But as I walk further through the gallery, my excitement wears off, and I start to be numbed by repetition. Perhaps this is part of their intention. I can’t help but ask: in not changing, are they missing something? Namely, the sense that ‘going against the grain’, beating your own path, means something very different today as it did in the 1960s. For a start, there is no ‘grain’ to go against. There are not paths of cultural evolution: it’s a web, in which we sometimes feel trapped, numbed by the words and images that surround us in the network era. Much of their work pivots on a juxtaposition and inversion of authorised and unauthorised discourse: graffiti and profanity alongside newspaper headings and government slogans. The distinction does not hold fast today. All writing is graffiti, and all is propaganda. No discourse is authorised any more than any other. And that is exhausting, to live in – and to look at, in art. I can’t help but be reminded of the guilt-ridden, social-media apathy that marks the moral landscape of my generation: torture, suffering, sign the petition; like, unlike, unsubscribe. They tell us their subject is the raw emotion of human experience: hope, love, sex, fear. But I don’t see these emotions so much as the idea of them. They are repeated and deferred, always just out of reach. They are speaking not (to me) of the human experience, but of the way that experience is abstracted and reiterated, spawning and breeding meaninglessly like AD Hope’s ‘teeming sores’. They don’t, in fact, speak to me at all, but only speak about speaking. But in doing so, they are, paradoxically, speaking about our modern malaise: about the way hope, love, sex, fear are trapped beneath the surface of the words and images, like a fly in a glass, trying to escape. This was prophetic in the 60s but now, we need to be shown the way out.

Gilbert & George

Born 1943 in San Martin de Tor, Italy and 1942 in Plymouth, England; live and work in London

Gilbert & George: The Art Exhibition, on display at Mona until March 28, 2016.

Photo Credit: Mona/Rémi Chauvin

Image Courtesy Mona, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia

I’m pleased to have had the opportunity to get to know the pictures better. The impressive scale of them, and of the artists’ commitment: this must be respected. But still, I want more. I think I’ve become a little old-fashioned. And I think Mona has the capacity to be that way, as well – to gravitate towards art that truly engages that moral dimension, even if, in doing so, it also shows us the darkest parts of ourselves.