Interview with ZEE artist Kurt Hentschläger

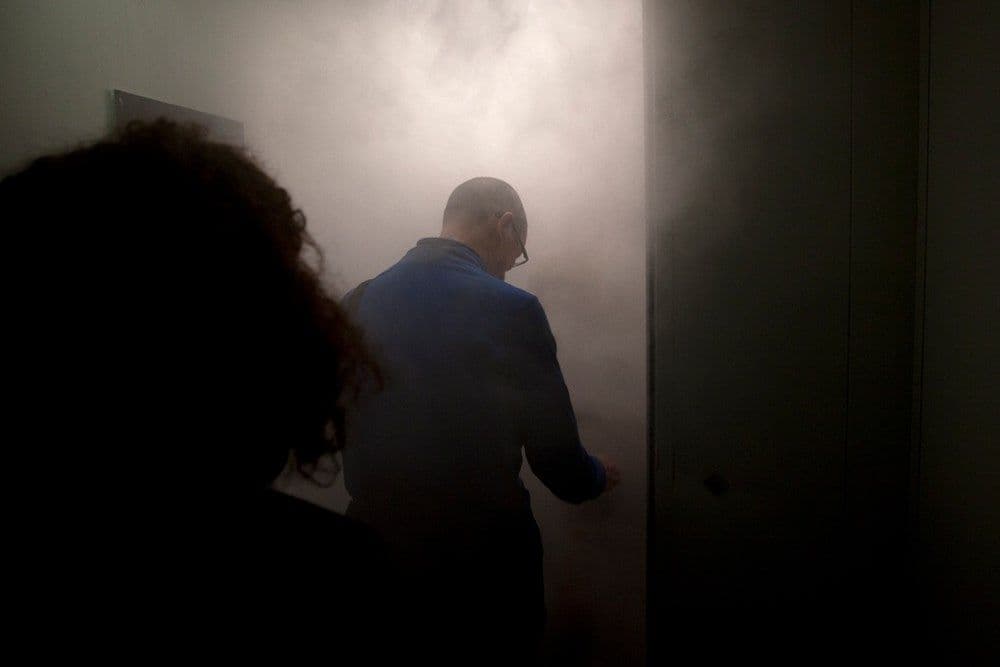

Inside ZEE

Photo credit: MONA/Rémi Chauvin

Elizabeth Pearce:

Are you surprised by the amount of people having bad reactions to ZEE?1

Kurt Hentschläger:

Yes. This is a very high rate. I'm not quite sure what to think of it. Usually, the statistics for photosensitivity – you can’t apply this globally because it must be different for different genetic groupings – in the States is one in four thousand people. That’s just generally, but for ZEE it’s much more, one in five hundred or so. The epileptic seizures are triggered by the flashes. It’s a very intense input, probably the most intense it could possibly be. In the first four days [of exhibiting ZEE in Hobart] we had three cases. That’s extreme. I’ve often contemplated whether I should stop showing it because I always dread that some day something really serious might happen. To have a seizure is very dramatic, but only a temporary event. It doesn't mean you’ll have epilepsy from this point on or anything like that, it just means you’re allergic to stroboscopic light at that intensity and at certain frequencies. All these things that you do to begin with – sign a waiver and take all the precautions – form one half of the work, and then there’s the other half, the actual piece, which is quite benign. Really it’s a beautiful piece about the experience of the sublime.

EP: So for you, the piece is more about the sublime than about being terrified?

KH: I have no intention to make a terrifying piece, that would be boring. It is an intense piece, there’s no question about that. It demands a lot from you in that you have to overcome the initial moment of – to say the least – trepidation, when you enter this strange world. But once you are in it, it can be quite elevating. I must remember that you haven’t seen it [because you’re pregnant and therefore not permitted entry].

EP: Yes. I only get to see the first half of the piece, the introductory framework. I’m sitting here watching these queues of people snaking out the door – they’re like lemmings going to their death. I have been wondering whether you are affected by the seizures, and obviously you are. So what keeps you going? Why keep showing it?

KH: That’s a good question. There’s a rationalisation of an impetus to keep going because, built deep into our concept of civilisation is an illusion of safety – the idea that we can control our environment and, at least to some extent, have stability. You question that the moment you decide to take a risk in life – to make a leap of faith to experience something unfamiliar. I could compare it to hiking in the mountains. The higher you go, the more tired you get, the less oxygen you have, the higher the risk of sudden weather changes and exposure in a spot where there's no shelter. The reward for taking the risk is that as you walk up you get this view – beautiful in the true sense. You're lifting yourself out of everything.

EP: Does that feeling of risk motivate you as an artist more broadly?

KH: Yes, I think so. I grew up in the original punk days, when it was all about exhausting yourself with a visceral, crazy energy. What’s interesting about overwhelming stimuli is not that you are overwhelmed per se, because this feeling you can easily have in any blockbuster movie – you get bombarded and you're excited, but then when you leave, you’re exhausted and you forget about it. This is an empty ritual of exhilaration, just to feel something. It’s not what interests me. What interests me is an emotional process, and a romantic notion of seeking to instil something that is bigger than life and that makes you see a wider concept or longer trajectory. In ZEE, what interests me the most is the idea of infinity. I often talk about perception, but it’s more about the habits than the mechanics of perception – the way we train ourselves from the beginning. Or maybe it’s better to say we don’t even train – it’s natural. When you're born you’re this wide-open vessel, and everything is just pouring in. But only those things close to you. You don’t learn to see past a certain distance until you get older.

EP: So it’s about a rerouting, even momentarily, those worn channels of perception?

KH: Exactly. You can only do this so much, though. When you come out you’re back in what you know and what we all agree is the world around us. But we do know there are other things to our existence, like when we dream or like deep meditation or drug experiences. I read this book [Trance: From Magic to Technology by Dennis R. Wier] that said that one way or another we are living in a state of trance throughout our lives. The author made a distinction between productive trances and destructive trances, like addiction. Or think about working on a computer – you forget about time and space and that you are hungry or need to pee or whatever. Eventually you wake up because your urges have become too great and you’re taken from your state of trance. So what I'm saying is that perception is a malleable process. We define it over time throughout our lives to again support our ideas of stability. Everything becomes a habit, a ritual; a loop that we adhere to. One of the things that I do like about ZEE is that it takes you out of that loop, just for a moment.

EP: Some of the ideas that we've been looking at in The Red Queen exhibition at Mona relate to that notion of a comforting narrative or illusion of security. You can take it a step further and say that our entire sense of the ‘I’, the self, is a fiction, the function of which is to create an illusion of stability and coherence. What you're saying is that you'd like to disrupt that illusion, to open a small gap for people to think in another way.

KH: Well, just to point to it. I have no expectation of making people change in big ways. That would be preposterous. But I think the important thing is that a lot of people find a strange joy in ZEE. I feel it still, even after all this time. Often when we’re installing there's a moment of true, deep joy for me. It must be related to the intensity of the light in a complete void – what feels to me like a space, or rather a sphere, of pure light.

EP: You’ve been exhibiting your work since 1983. Did you know at that time what you wanted to achieve?

KH: No, but I did have clear interests. I did a body of work in those days with absurd machines, like machine sculptures. Then in ’89 I got my first computer and that changed my whole idea about the process of art making. I stopped drawing, for instance. [Visiting The Red Queen exhibition] was very inspiring because I saw a lot of drawings that I really liked. The drawing machine [by Cameron Robbins] is absolutely fantastic, and I think I have to pick up drawing again. Like, a hundred years later, go back to where I started.

EP: Technology is obviously a very important part of your work. Do you feel unfettered celebration about the speed at which technology is evolving? Or do you ever feel a sense of alarm?

KH: Yeah. I'm sick of it. I will not develop software anymore. I'm not going to go into any more serious engineering efforts because they take so much time and I think it often leads to an imbalance, where the technology is only half expressed, and the content itself is also half expressed. A long time ago I thought that what is now called ‘new media art’ was very interesting and exciting. There was a challenging discourse and so many brilliant people, and the scene was very experimental. Everything was wide open. Now, with the process of institutionalisation, there's much more of it but a lot feels quite empty. Nowadays, if I order a computer or related tool I'm already annoyed because I know when it comes I will spend all this time preparing it, setting it up, checking whether it works and so on. Of course it’s part of the craft and I do think media technology is my particular craft. There's no question I know a lot about it.

EP: You've grown with it, really, from the 80s onwards.

KH: I often say when I teach – and I don't even mean it as a joke – that I come from before time. I was eight years old when my family got its first television. I've seen the whole thing come in ever-faster cycles. You can spend your whole day just trying to keep up. But of course, on the positive side, it is a huge and very powerful toolset and opens aesthetic possibilities that I still find interesting to some extent.

EP: It's reconfigured, over the space of one generation, our very consciousness, our engagement with reality – language, thought, time and space.

KH: That was a very acute sense of mine in my mid 20s, even before I got the computer – that this would change pretty much everything. I wanted to inundate myself because I thought, ‘This is going to be the world, and I must know about it if I am going to be able to make any sort of informed artistic statement about it’. My early pieces with [audio-visual art collective] Granular-Synthesis – particularly Model 5 (http://www.kurthentschlager.com/gs.html?utm_source=mona.net.au&utm_medium=referral) – were these single-frame, edited, resynthesised human heads. They were very intense, very aggressive, brutally loud. Model 5 would have been completely impossible without a computer. We used a non-linear editing system that had just come out. The system was a complete game changer, allowing us to do things in a month that would have taken maybe two years. So in that regard, certain technologies really bring about aesthetic progress, or certainly accelerate aesthetic processes. I don't know whether it's meaningful progress, but –

EP: The question of progress is a difficult one.

KH: Yes – whatever progress is. But this interest in what these media machines and networks will do to change the world, to change our behaviour, to change everything, has formed into the question: How do we operate and perceive to begin with? As for our immediate future it’s clear what will happen. It’s going to go further, and eventually there really will be cyborgs. Currently, everybody has this blue glow in their face [from the screen of a smart phone]. At the moment this [smart phone] is state-of-the art, but it's still awkward. You have to carry it still. There will be something that will be smarter and more merged with the person.

EP: I admire what you said before about how when you first started getting into technology you decided to completely immerse yourself in it. I'm not interested in technology. How something like that works doesn't capture my imagination. It’s a bit disturbing that I'm using things that are fundamentally changing my life, without understanding how. It happens, magically, inside the black box.

KH: Yeah, but on the other hand there are lots of things we use that we don’t understand – I was never interested in knowing how exactly a car works. In the beginning there were these huge boxes, modems, on the telephone that made these funny noises when you connected. It was very slow and there was always something not working, so you had to know a lot in order to be able to fix things quickly. But ultimately, like I said before, it takes too much time. What I want to do now for a while is wilfully slow it down, not change. Dig in, and work on something until it becomes substantial. I think at the end of my life I'm going to be a photographer and musician. I want to learn the accordion. I’d like to do something with my hands – direct, rather than just sitting in chairs, making these minimal, almost disembodied movements with a mouse.

1 Since opening on June 14, 3185 people have visited ZEE; ten have required medical attention as a result.

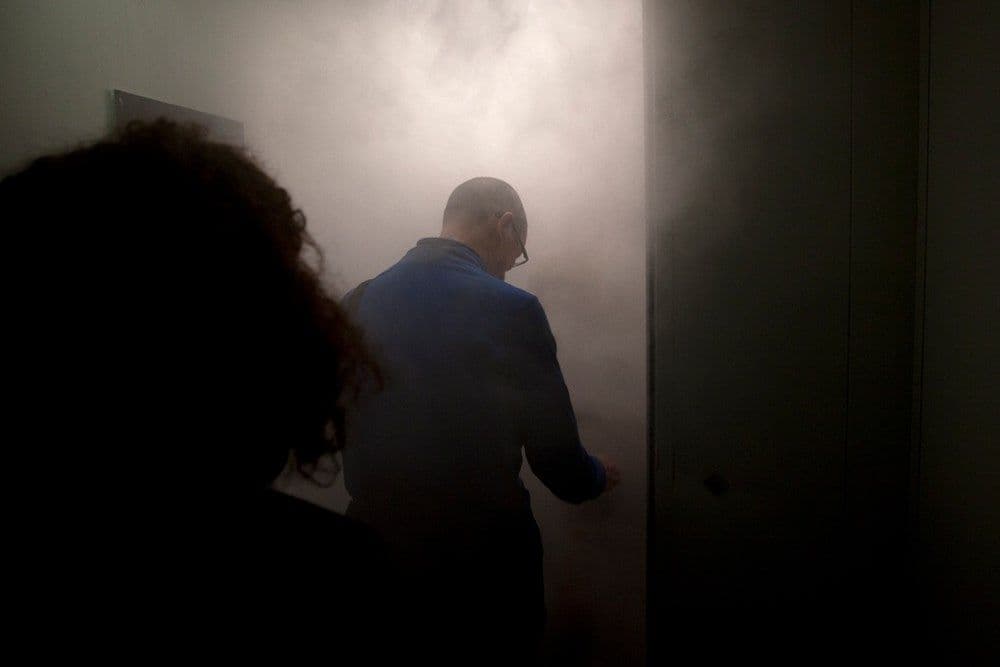

Entering ZEE

Photo credit: MONA/Rémi Chauvin