The Museum of Everything

We asked The Museum of Everything to come and occupy Mona. But the result—like everything, always, everywhere—is up for debate. Is it an occupation, or a collaboration?

The Museum of Everything is a travelling institution, which opened in London in 2009. Its purpose is to advocate for the visibility of art that falls outside the confines of the artworld proper; the work of ordinary people, working far (literally or otherwise) from the cultural metropolis.

That word, ‘ordinary’, is an interesting one. Because oftentimes, the art that we are talking about—let’s call it the art of everyone—happens to be made by people who can only truthfully be described as extraordinary.

These artists don’t have degrees, but they might have visions or compulsions; they are transcendent scientists, self-taught architects, and citizen inventors; sometimes, they are dedicated followers of personal belief systems, or producing art from inside a hospital or prison. Some create their own visual folklore to sit alongside (or challenge) established histories of culture and place. ‘Our museum stretches, I hope, the possibility of who has the right to be considered an artist,’ says founder James Brett. But of course, not everybody is an artist. The collection comprises the passionate fringe, the outliers who concentrate the human propensity to make and create. They are simultaneously different, because that kind of intensity and ability is not available to us all (and especially not in the absence of the usual artworld rewards, such as money and cultural cachet), and yet they are also somehow the same, more familiar to us than the big artworld names will ever be.

This extra/ordinary tension complicates the category ‘art’, in its deepest sense. Is art typical, universal, even biological—or is it exceptional? Can we place elite art, that which is clearly tied to the desire for social status, next to apparently private forms of creative expression, and call them by the same name?

To answer these questions, as well as the important social-justice ones that accompany them, you must first widen your concept of art. It stops being about insider/outsider, us and them, and becomes instead a big, wobbly, cumbersome carryall; and once ‘everything’ is included, nothing is, and so the whole problem of terminology and definitions just dissolves, until you’re left with nothing but an action. The will to make thrives everywhere, even in the most unlikely places. That’s what our friends at The Museum of Everything are trying to show. And we want to help them, in the form of this exhibition. The occupation is an invitation.

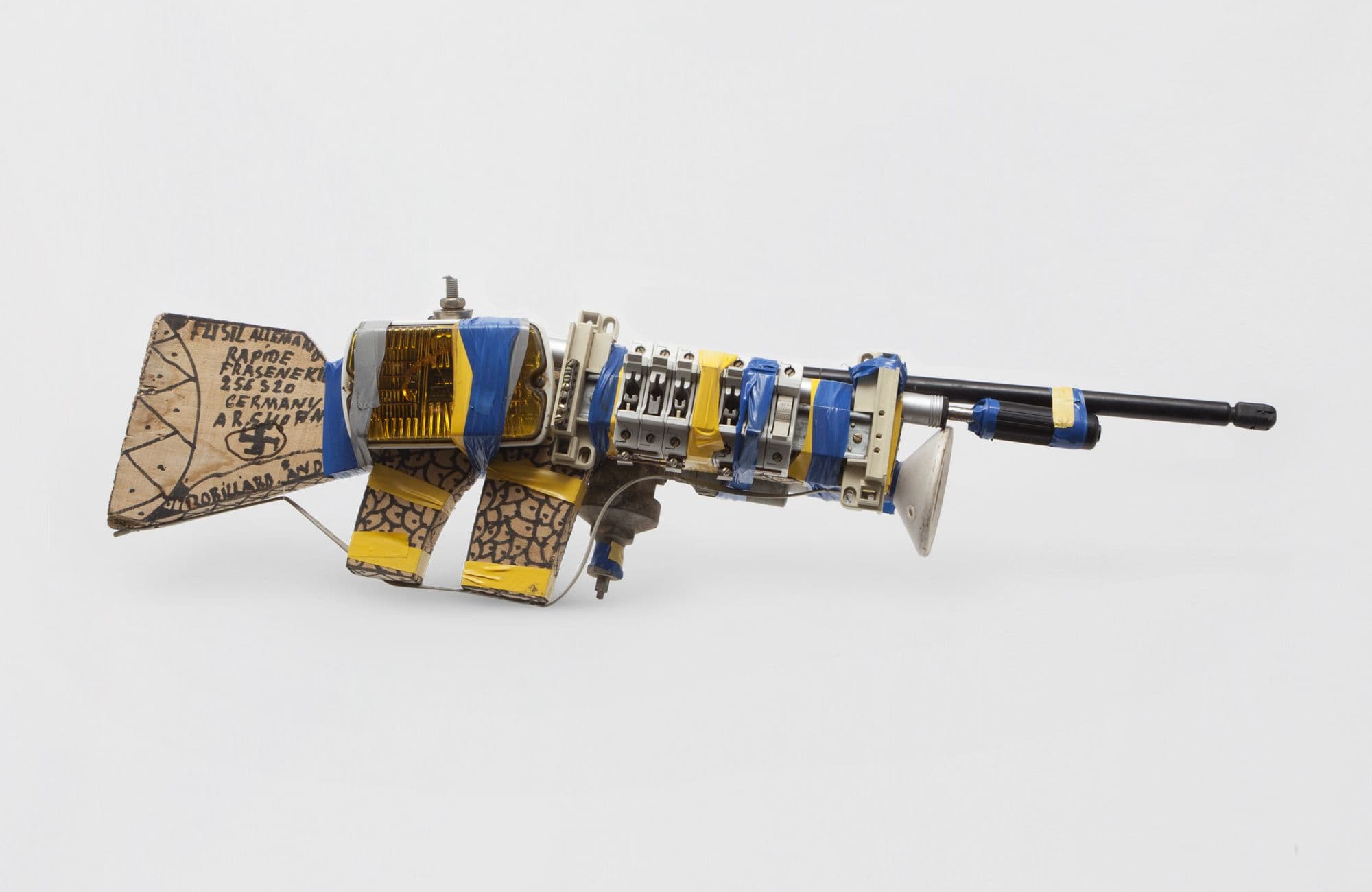

What you will find, when you come, is a jolly fine collection, cor blimey, of drawings, paintings, sculptures, photography, environments and assemblies. There will be wondrous samples of the Art Brut/Outsider Art canon (oh, the irony) as well as the ‘newly discovered’ (as our British imperial overlords would have it), alongside work from studios for artists with disabilities. We’re excited. This stuff matters, in a social-justice sense and in an art-lovers sense (we’ve been missing out!). But also, we empathise—being from Tassie and all—with the whole outsider/insider thing. Specifically, the problem: what happens when the outsider becomes the institution; the exception, the rule? Is it even a problem?

Both our museums—that of Everything, and of Old and New Art—want to learn, in the most human of ways: by doing. ‘The hand is the cutting edge of the mind,’ says Joseph Bronowski. Art, in the end, is a behaviour, something we can’t help but do—or at least, it should be. The best way to test its mettle is to clear away the extra stuff, the artworld beatifications, the labels and classifications, to see what’s left. You might just find it’s everything.

Artists:

ACM (Alfred Corinne Marié)Alikhan AbdollahiHorst AdemeitHilma af KlintAlbertAlmighty God (Kwame Akoto)Noviadi AngkasapuraMary BarnesMorton BartlettGeorge BecksteadAdelhyd van BenderPeter ‘Charlie’ Attie BesharoForrest BessBenjamin BinderIon BîrlădeanuAaron BirnbaumCalvin and Ruby BlackEmery BlagdonPearl BlauveltReverend William Alvin BlayneyJulius BockeltErich BödekerHawkins BoldenUwe BrecknerFreddie BriceHerman BridgersAníbal BrizuelaDavid BurtonMarian Spore BushRaimundo CamiloTom Carapic (Tomislav Sava Čarapić)James CastleNek Chand (Nek Chand Saini)Brian ChinMamadou CisséClive CollenderFelipe Jesus ConsalvosAlan ConstableAloïse CorbazJoseph Crépin (Fleury-Joseph Crépin)Francesco CusumanoRichard DaddHenry DargerCharles A. A. DellschauLouis DeMarcoJames DixonHiroyuki DoiJim DornanSam Doyle‘Uncle Pete’ Drgac (Peter Paul Drgac)William EdmondsonWalter EllisonMinnie EvansDenis EzhikovGuo FengyiChase FergusonGiovanni FicheraReverend Howard FinsterAuguste ForestierVerba FrazierGiovanni GalliWillem van GenkHans-Jörg GeorgiPietro GhizzardiMadge GillRichard GreavesDaniel GreenPeter HandWilliam HawkinsHosea HaydenManfred HenkeMorris HirshfieldStan HopewellGeorgiana HoughtonReverend Jesse HowardWilliam HowardHector HyppoliteEnrico ImodaVladimir IsaevKarl Hans JankeAlfred JensenWillie JinksReverend Anderson JohnsonS. L. Jones (Shields Landon Jones)Karl JunkerJuva (Prince Antonin Juritzky)Peter KapellerRoland KappelKatyusha (Ekaterina Skvortsova)John Urho KempBodys Isek KingelezZdeněk KošekNorbert H. KoxJulia Krause-HarderHans KrüsiViktor KulikovPaul LaffoleyDominique LagruPavel Petrovitch LeonovAugustin LesageLarry LewisGeorges LiautaudAlexander Pavlovitch LobanovAlbert LubakiLeonid LugovykhPascal-Désir MaisonneuveAnthony MannixAbu Bakarr MansarayJulian MartinKunizo MatsumotoJustin McCarthyJohn Patrick McKenzieMalcolm McKessonAleksandr Medvedev-PetrovM.E.N. (Melvin Edward Nelson aka Mighty Eternal Nation)John MilesDan MillerG. T. Miller (George Thaxton Miller)R. A. Miller (Reuben Aaron Miller)François MonchâtreSister Gertrude MorganWilliam MortensenJ. B. Murray (John Bunion Murray)Masahiko OoeDietrich OrthFrancis PalancMichael Patterson-CarverJean PerdrizetAlcides Pereira dos SantosReverend B. F. Perkins (Benjamin Franklin Perkins)Reverend Samuel David PhillipsElijah PierceMaster Pixilô (Manoel Francisco Dias)Francisco Ponte (Francisco Ponte Jiménez)Walter PotterAlevtina Dmitriyevna PyzhovaJosef Karl RädlerMartín RamírezRobert RapsonÉmile RatierW. C. Rice (William Carlton Rice)Prophet Royal RobertsonAndré RobillardWilliam Rice RodeVasily Tichonovich RomanenkovYuichi SaitoNicolò ScarlatellaHans SchärerPaul K. Schimmack (Paul Karl Schimmack)Friedrich Schröder SonnensternJudith ScottWilliam ScottSava SekulićTomoyuki ShinkiMary T. Smith (Mary Tillman Smith)Janet SobelAustin Osman SpareL. C. Spooner (Lee Cordova Spooner)Harald StoffersMarcel StorrIonel TalpazanKatsuhiro TeraoJames ‘Son Ford’ ThomasMartin ThompsonWilliam Thomas ThompsonMiroslav TichýBill TraylorLyudmila Aleksandrovna TrunovaJohn VanZileLouis William WainAugust WallaAlfred WallisMelvin WayMyrtice WestGeorge WidenerTerry WilliamsScottie WilsonJosef WittlichClarence and Grace WoolseyAdolf WölfliWilliam WurffleinJoseph YoakumGiuseppe ZafaranaAnna ZemánkováBogdan ZiętekCarlo ZinelliAloys Zötland many anonymous makers

Header image: Untitled, c. 1990, André Robillard. Image courtesy of The Museum of Everything